Grid Gentrification

The problem with AI data center power demands isn’t the amount, it’s the location.

Data centers are drawing growing concern over their enormous appetite for electrical power. However, the real problem isn’t their total usage. Rather, it’s where they concentrate power demand and how they impact local markets.

A common story today is that AI is a wasteful power hog. However, that story misses the real problem. Currently, data centers use only about 4.4% of US electrical power generation (176 TWh / 3,874 TWh, DOE) and less than 1% of total US energy use (18,000 TWh, EIA). Yet they contribute an estimated $3.46 trillion to the US GDP (PwC, direct, indirect, and induced economic activity). Data centers generate about 11% of economic output for less than 1% of power usage.

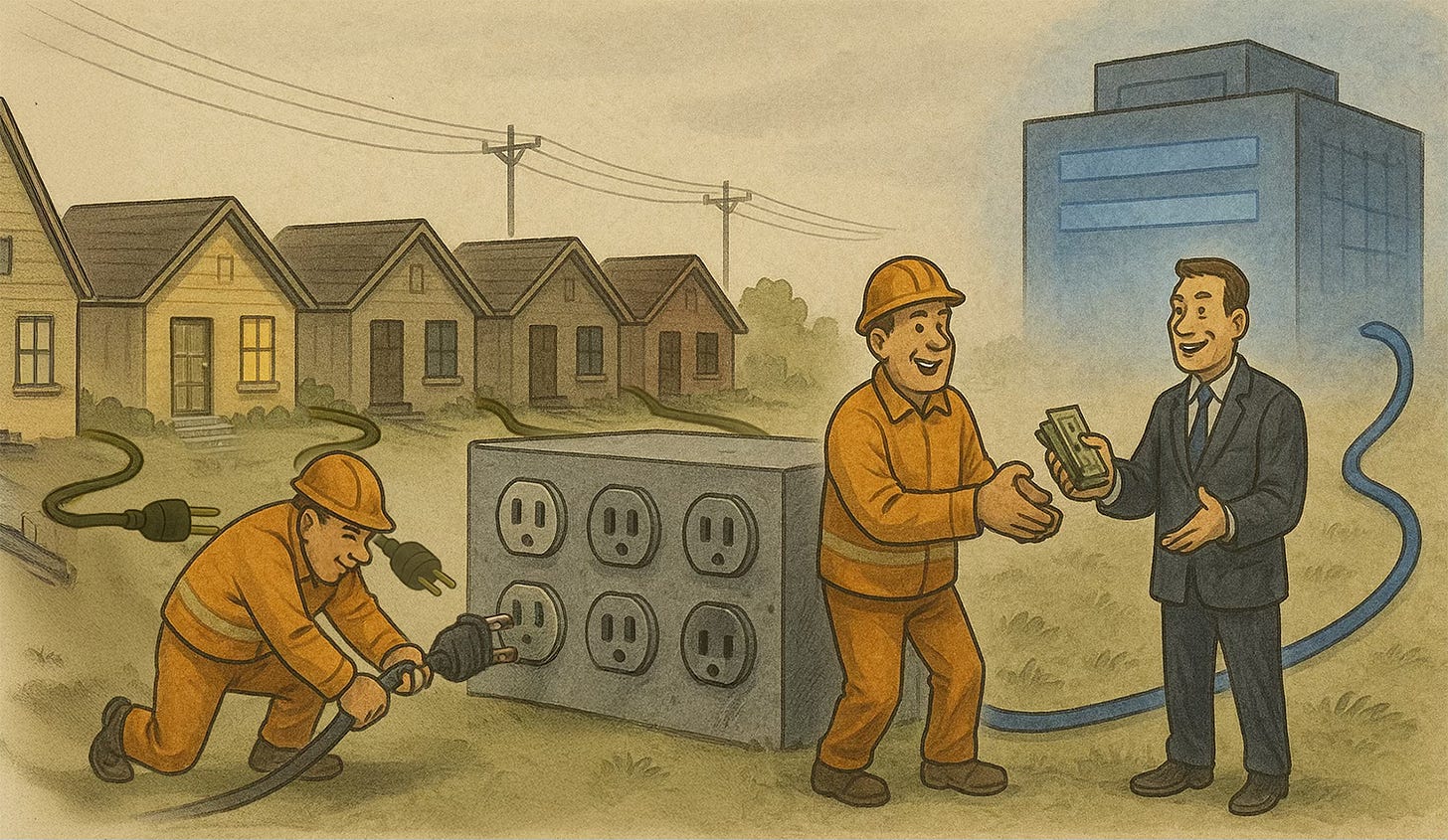

The real problem is not waste, it is wealth. AI workloads are so profitable per kilowatt of electricity that data centers can afford to pay far more for power than nearly anyone else. That purchasing power is beginning to distort local energy markets, displacing ordinary consumers. The result is grid gentrification.

The term “gentrification” usually refers to what happens when a low-income neighborhood becomes attractive to wealthier home buyers and the original residents are priced out of their homes. Grid gentrification works the same way, but with the power grid rather than real estate. When rich data centers move in, residential users can end up priced out of electricity.

The average U.S. household pays about $0.17 per kilowatt-hour of power, and a typical family uses about 855 kWh per month (Palmetto), which works out to an electricity bill of $145 per month. If rates doubled or tripled, less affluent people would have to give up air conditioning, electric heating, hot water, or cooking. At five or ten times the current price, basic modern living would become unaffordable for many.

Now consider the economics of an AI data center. A cloud compute provider can rent an NVIDIA GH200 superchip system for about $3.19 per hour. According to NVIDIA’s benchmark guide, the GH200 draws roughly 1 kilowatt of power at full load (900 W GPU + 100 W CPU and memory, NVIDIA Benchmark Guide). At current residential rates, running one GH200 for an hour would consume about $0.17 worth of electricity, plus perhaps another $0.10 for cooling and $0.09 for maintenance and other costs. This means that the data center could clear nearly $2.80 profit per hour, or roughly $24,000 per year, from that single kilowatt of capacity.

The implication is that the data center could easily pay five to ten times the residential rate for power and still make money. In a constrained power grid, data centers can afford to outbid others in order to get the power they want. This drives up wholesale prices and makes residential electricity less affordable.

Making matters worse, utilities often must build new transmission lines for large customers, with costs spread across all ratepayers. Households not only face higher prices but subsidize the infrastructure that enables their displacement.

The fix is not to demonize AI or attempt to limit computing progress. Instead, we should price electrical power in a way that benefits society while still allowing technological progress. Data centers should be responsible for their own transmission upgrades and they should pay higher per-kilowatt charges that reflect their disproportionate ability to pay. Differential pricing would incentivize conservative power use by data centers and prevent them from buying power out from under everyone else.

Local governments resist such measures, seeing data centers as economic wins. Unfortunately, once built, data centers employ few people and contribute little locally (Business Insider). Officials expecting economic development get disappointing benefits while residents face larger electric bills.

If oversubscribed power regions implement differential pricing, AI companies will either absorb the cost, channeling money into local economies, or locate to regions with abundant power. Both outcomes are preferable to the current situation.

At a time when AI automation is already displacing workers, data centers should not be creating further strain by inflating residential power bills. Charging data center operators premium rates for electricity would help reclaim some of the revenue lost to automation.

Differential pricing is just one possible way to prevent data centers from displacing existing electrical customers. We have already seen what happens when housing markets become distorted by gentrification. If we allow the same dynamic to take over our electrical grid, we may find ourselves priced out into the dark while our machines keep their lights on.

About Me: James F. O’Brien is a Professor of Computer Science at the University of California, Berkeley. His research interests include computer graphics, computer animation, artificial intelligence, simulations of physical systems, human perception, rendering, image synthesis, machine learning, virtual reality, digital privacy, and the forensic analysis of images and video.

If you would like to read my other articles, consider subscribing. You can also find me on LinkedIn, Instagram, and at UC Berkeley.

Disclaimer: Any opinions expressed in this article are only those of the author as a private individual. Nothing in this article should be interpreted as a statement made in relation to the author’s professional position with any institution.

This article and all embedded images are Copyright 2025 by the author. This article was written by a human, and both an LLM (GPT 5) and other humans were used for proofreading and editorial suggestions. The editorial image was composed from AI-generated images (DALL·E 3) and then substantially edited by a human using Photoshop and Adobe Firefly.